At first, planes circled over their village. “We saw the planes but didn’t know what they meant.” This was around ten years ago. Christine Nyangoma, four children, single parent, is a petite woman. She wears a sparkly dress and ponytail. In a tired voice, she talks about what has happened since 2012.

After the planes, came officials from the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum Development. They called a community meeting in the village near Lake Albert in Uganda. The land was needed for the construction of a refinery - and for Kabaale International Airport, a new hub for the region where oil is to be produced from 2025. In 2012, there were huts, barns, goats.

Today you can see a levelled moonscape here, which will later be the runway. The men would have promised compensation or resettlement in a new house with land, according to internationally recognised standards. All the people would benefit. “The promises were so big,” Nyangoma says.

But promises are a tricky business. On the one hand: 1.2 to 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil, 220,000 barrels are to be pumped out of the ground every day - in Russia, the average is 10.1 million. On the other hand, a country where the average monthly wage in 2020 was equivalent to 53 euros, with 70 per cent of workers based in agriculture. On the one hand: more than ten billion dollars in total investments, better roads, the hope of a little more participation in the world market, where the price of oil is rising sharply again. Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni promised that the economy could grow by ten percent a year from the start of oil production. Energy Minister Mary Goretti Kitutu spoke of more than 160,000 new jobs. On the other hand: tens of thousands like Nyangoma who are losing their homes or land for the oil - and the doubt as to whether the newfound prosperity will ever reach the population.

Between the oil deposits at Lake Albert in western Uganda and the sea in Tanzania, where the oil is to be loaded onto tankers, lie national parks and some of the most biodiverse areas on the planet. Environmentalists say: Irresponsible! And: If we develop new oil deposits now, the 1.5 degree target will become impossible and the climate consequences even worse, especially in countries like Uganda, which is already severely affected.

The French oil company Total, the Chinese company CNOOC and the governments of Uganda and Tanzania are developing the oil deposits at Lake Albert nonetheless. In Uguanda, to get the oil to the sea from the two production areas at Tilenga and Kingfisher, the consortium is building the longest heated crude oil pipeline in the world, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP): 1,443 kilometres to Tanga in Tanzania on the Indian Ocean.

The final investment decision was made in February 2022. If you look at the geopolitical map, it becomes clear: it could be the beginning of an oil boom in the whole region. And because Europe no longer wants to buy oil from Russia due to the invasion of Ukraine, African oil becomes even more attractive.

What does such a large-scale operation mean in a country that, according to the United Nations Development Index 2020, ranks just 159th out of 189? What of the warnings from human rights and environmental organisations? We spoke to people on the ground. The picture that emerges is less glamorous than the brochures of the energy companies.

The Displaced

Christine Nyangoma is one of the people referred to in company and government documents as “PAP”, “Project Affected Persons”. Oxfam estimates that 60,000 people in Uganda and Tanzania will be affected by the pipeline alone; the Ugandan NGO Afiego estimates that at least 100,000 will be affected by the pipeline and oil production; the French NGO Amis de la Terre estimates that more than 117,000 will be affected. On request, Total mentions 18,800 PAP in the Tilenga production area and through EACOP, only 723 of whom would have to be resettled. However, according to the definition of the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank, a PAP can also mean a household.

In addition to the airport, an oil processing plant and a small refinery for national needs are to be built in Kabaale. Many of those affected here opted for money instead of resettlement. So did Christine Nyangoma’s husband at the time. Then he disappeared with the compensation. To this day, she does not know where he is.

There are many women like her, Afiego reports. In Uganda, most of the land is traditionally in male hands and passed down from fathers to their sons. Only 15 percent of women have property rights, according to the UN organisation FAO. However, compensation for land, crops or houses would be paid to the respective principle owners.

After all, Nyangoma owned a small piece of land, paid for by savings from her work as a seamstress. She chose the option of resettlement for herself and the children, together with 93 other families from the former village.

The new village is called Kyakaboga Resettlement Village and is a good 15 kilometres away from the old settlement. Those who want to get there have to drive over dusty roads. The red soil is barren. Even from a distance, you can see a straight line of yellow houses with red roofs on a hill, all identical in construction. Christopher Opio has his office in one of the houses. He founded a residents’ association after his family was resettled. He says: “The new settlement has nothing to do with the traditional way of life.”

Before moving to the replacement settlement, they had to wait. The school was already closed in 2013. “At some point, the village resembled a ghost settlement with only a few inhabited houses,” Opio recalls. The remaining inhabitants were told to grow only crops on their land that could be harvested after a short time.

The problem: 39 percent of agriculture in Uganda is subsistence farming. Many fields are more like forests than German cornfields. Plants like plantain, cassava or jackfruit are perennials, bushes and trees. It often takes years before they bear fruit. Human rights organisations criticise that the loss of these harvests, also at other locations of the oil project, has led to food insecurity and loss of income.

The replacement settlement was only completed in March 2018. Residents were not allowed to have a say in where it was built. And what was built there “is more like a camp than a village”, says Opio. He invites us into his office and sketches how families lived before: each on their own land in the middle of their own fields. Other small buildings, pantries or stables were grouped around the main house. When a son turned 18, he got his own hut on the property. Several generations lived together like this.

After resettlement, all families received a standard house as a replacement - three small bedrooms, a tiny bathroom, a living room, a cooking area and latrine behind the house, only a few metres away from the next house. This leads to conflicts, says Opio: goats run across the neighbours’ property and eat cassava that is lying in the sun to dry. There is no space for tools, no privacy for young people. And if someone steals from the fields at night, no one wakes up. Some villagers therefore built an additional hut in the middle of their fields - at their own expense.

Christine Nyangoma did not get a replacement house, because there was no house on her piece of land before. And her ex-husband was compensated for the house she lived in. So she had to build her new mud house herself. The village community helped her. It is no bigger than 30 square metres.

In the anteroom she has her sewing station, with a mechanical Singer sewing machine on which she tailors school uniforms and dresses. She pays the school fees for her children from the income. And they often help in the fields after school, like an average 28 percent of all children in Uganda. The field is now one and a half kilometres away from the house, and they transport tools and crops on foot or by bicycle.

After the move, the next shock: in 2019, the government had announced that this land would also be affected by oil production - through a feeder pipeline for the oil wells in the north of Lake Albert. “I thought I was safe when I came here,” she says. “But when you live near the pipeline, you never know what will happen next.”

The Resistant

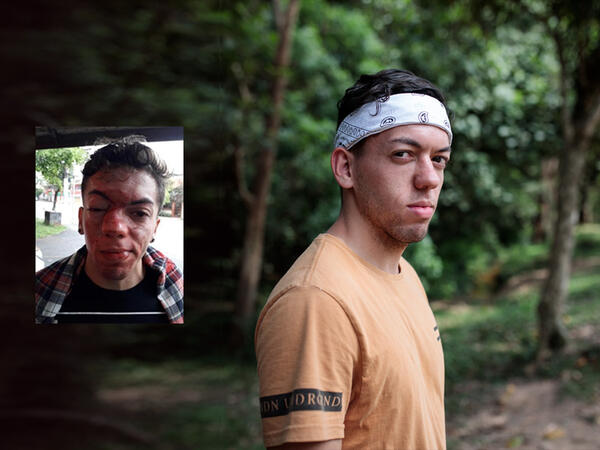

Jelousy Mugisha has decided not to put up with it all. The tall, gaunt man lives in Buliisa district, a little further north. The majority of Ugandan people affected by oil are here. With 423 wells, Total will produce most of the oil here in the future, up to 190,000 barrels a day. Because he thought the compensation offered was far too low, Mugisha testified in court. First in Uganda, then in France. The result: intimidation and to this day no new home.

Mugisha has built a temporary home for himself, his wife and children on a small piece of land owned by relatives. Visiting him is complicated. The route traverses bumpy side roads, since there are checkpoints on the main road to Buliisa, and there are many security guards present throughout the region, some from the government, some from private security firms on behalf of the companies. “We can’t go through there with cameras in the car,” says the local activist showing the way. If he showed up at the checkpoint together with whites, it would be immediately clear what was going on. Because criticism of the oil project is not welcome. Too many have been threatened, arrested and intimidated when they speak critically about the large-scale project.

Mugisha says he was not offered a replacement for his home, but cash. This is because his house was classified as a second home. 12.5 million Ugandan shillings, which is about 3,300 euros. But he wanted a new house if they were already taking his. And for that money he could not build a new home somewhere else. So he protested. The subcontractor responsible for the land requisitions referred his case to Total, then to a Ugandan court. They ruled against him. “We are not trying to sabotage Total’s project,” he says. “But they must take our rights seriously.” Because Mugisha did not succeed with his demand, he testified against Total in France - as part of a lawsuit filed by the Ugandan NGO Afiego and the French Amis de la Terre. Until now, it has usually been easy for international corporations to operate in Africa: If there are problems, they can shift the responsibility to subcontractors. Since 2017, however, a new supply chain law, the loi de vigilance, has allowed the economic profiteer at the end of the chain to be prosecuted. Upon returning, Mugisha was immediately arrested by police at Entebbe airport. “Why are you going to court in France when we also have courts in Uganda?” they had asked. “We are warning you seriously, don’t do that again.” He was released without charge that evening. Later, he had received anonymous threatening phone calls. The case is still open. He will remain without a home in the meantime. Total does not comment on the specific case, but only in general terms: The company does not tolerate threats against those who peacefully defend human rights.

The Water Carriers

It is difficult to independently confirm the testimonies of local people. But there are too many incidents like those of Nyangoma or Mugisha to see them as isolated cases. Oxfam conducted a study in Uganda and Tanzania and interviewed 1,211 people from 36 villages. The result: compensation came too late, evaluation standards were not easy to understand, there was a lack of transparency.

Some of the problems lie literally by the roadside. While the airport, boreholes and processing plants are being built and the pipeline is not yet visible, the new roads cannot be overlooked. To transport gigantic amounts of materials and labour, the Ugandan government is building so-called Oil Roads through the regions along Lake Albert. A large part is already finished.

The brand new paved roads are a rare sight in Uganda, where most people transport everything from chickens to banana plants by foot, bicycle or motorcycle taxis. The roads are Uganda’s down payment to make it easier for oil companies. They are touted to the population as a forward-looking development for the country. And indeed, the roads are wider, smoother and cleaner than some European motorways.

However, the government has borrowed some of the money from Chinese donors, and only some of the roads are being built by the oil companies themselves. If oil production did not work out in the end, the country would be left with its debts.

Those who drive along the roads are mostly alone. Apart from large trucks with construction materials and oil company pick-ups, there are only a few motorbikes and schoolchildren walking to the next village. The builders apparently did not plan for a kerb for pedestrians.

And in many places the roads have unexpected repercussions. In the settlement of Nyairongo, for example. Next to the motorway, which lies on an embankment, the road descends a few metres. Down there, women and children use cups and bowls to scoop water into neon yellow canisters from the brown rivulet that emerges from under the road. Numerous families live from this water. Fixed pipes are usually only in the cities, and even there not everywhere.

One of the women at the water point is Aisha Tumuheirwe. The water here has been flowing less since the road was built, she says. The road authorities promised to build a new, better source, says another villager.

The new wather source does exist, a few metres further on. A pond has formed, goats graze on its banks. But water that is used for drinking must flow, say the people here. Too many germs collect in stagnant water. So most of them fetch their water further along the road.

The water problem runs through the region like the newly drawn roads. A few kilometres further on, the village head of Bwendero Village complains. In his community, there is a clean, captive spring. A rare luxury. But on the oil road that runs through his village, so much water collects during the heavy rains that is typical of some months that holes are washed into the paths through the village. This has made it much more arduous to get downhill to the spring. And the promised side roads that were supposed to connect village paths to the new main road have not been built either. The government has not responded to his letters, he says.

The Keeper

When ranger Lilian Namukose reaches for her binoculars, she has spotted something. She points to a tree next to the sand track in the national park. A leopard is sitting motionless on a branch, returning her gaze. Namukose wears spotted camouflage clothing and sturdy leather boots, she has a rifle slung over her shoulder for emergencies. She has been working in Murchison Falls National Park since 2016. It doesn’t take long before the first buffalo walk past in plain sight. An older elephant is out alone in the early hours of the morning, plucking leaves from the tree. Behind it, a herd of antelope grazes.

Murchison Falls is Uganda’s oldest national park, covering more than 3,800 square kilometres. It is named after the mighty waterfalls in the east of the park, where the Nile plunges more than 40 metres into the depths. The park is also located in the Buliisa region. It begins about ten kilometres from where Jelousy lives.

The animal population has just recovered, Namukose says. Under the former dictator Idi Amin, there was a lot of hunting. During the Ugandan civil war, rebels set up hideouts here and supplied themselves with game meat. It was not until the 1990s that peace slowly returned.

Today, more than 2,700 African elephants are back living in the national park. It is home to leopards, giraffes, hippos - 76 different species of mammals. The kob antelope, Uganda’s heraldic animal, is particularly common. And the wetlands along the Nile are home to 451 bird species, many of which are endangered.

However, climate change is causing problems for nature. In 2020, when heavy rainfall caused severe flooding at Lake Victoria, the shores of the national park also overflowed. “Crocodiles could no longer find a place to lay eggs,” says Namukose. “Birds could not nest in the trees because they disappeared under water.”

Conservationists are worried about something else: oil is to be extracted in the national park in the future. Ten of the 34 drilling stations of the Tilenga project are located in the park. Total’s response is that they have limited the number of sites as much as possible, only 0.05 per cent of the park area is affected by the project.

The road from the entrance in the southeast through the park will also be upgraded and paved. The first part of the road through the forest is finished, with roadkill monkeys lying on the side of the road. Those who cross the Nile later will no longer cross by ferry, but will take the new multi-lane bridge. Trucks drive here every day to get to the construction site in the savannah part of the park.

Conservationists predict that many animals will no longer dare to cross the new road when the sun heats up the asphalt. They have already been observed avoiding the trucks and construction workers in the vicinity. Scientists working for Total studied how elephants changed their migratory behaviour as a result of the test drilling. Analyses have shown that the animals react to boreholes and seismic activity “by moving away for the most part”.

When wild animals leave their previous environment, this can lead to new conflicts. The national park is not fenced. Elephants are now seen near villages more often, residents say. And not only can they trample crops and eat supplies, but also attack people who get in the way.

So is it the case that those responsible have not sufficiently considered the potential ramifications? The park ranger prefers not to talk about the state-sponsored oil project. She says only this much: parts of the park have been affected, pressure has been put on nature. “Every development goes hand in hand with destruction.” She hopes that “those responsible would have already taken the necessary precautions” and that the park she wants to preserve will not be affected. “We trust them,” Namukose says. “We are trying to trust them.” She hesitates for a moment. “We really try to trust them.”

Total’s Tilenga oil project, which includes the boreholes in the national park, was incidentally named after the local name for the Ugandan antelope that lives in the park.

The Fishermen

The Chinese part of the drilling project has also found its inspiration in nature. Kingfisher, as the extraction area along Lake Albert is called, is the name of a rare bird that lives in the wetlands. The bright blue bird feeds mainly on fish. So does a large part of the local population.

When Morris Ouchi moved to Kaiso on Lake Albert 18 years ago, business with the fish was good. He invested in some mopeds to supply to the region. The lake, through which the border between Uganda and the Congo runs, stretches over a length of 170 kilometres. It is home to more than 45 species of fish, including Nile perch and tilapia. 30 percent of Uganda’s fishing haul comes from this lake.

But the fish have become fewer, says Ouchi. Under his guidance, a group of young men are building a new wooden boat. Colourfully painted boats lie on the lakeshore. The men on the beach are repairing nets, little boys are rowing out onto the lake to cast their fishing rods. When he arrived, only a few people lived in Kaiso, Morris says. But the population has grown a lot and the lake is now overfished, he adds.

He points to one of the houses half-submerged in the water. When there were floods on Lake Victoria two years ago, the water level rose here too. Not far from where a palm tree now stands in the lake, test drilling had previously taken place. The result: a large part of the oil deposits are under the lake.

What impact will it have on the local fishermen if oil is extracted along the lakeshore in the future? Ouchi thinks for a moment. So far he has only heard rumours. Maybe they will have to clear the lakeshore once the oil business starts. He cannot verify whether this is true or not.

The biggest disaster for the people here would be oil leaks directly at the lake. But the 1,443-kilometre pipeline also crosses several wetlands and rivers.

Environmental organisations and opponents of the project point to Nigeria, where oil production has caused soil and water pollution for decades. Or Ecuador, where another pipeline burst just a few weeks ago. Total says that most of the pipeline runs underground and that it is constantly monitored with the help of fibre optic cables along the pipeline. Environmental activists say: a great many oil wells have long-term leaks.

In March, the Ugandan government published a plan of proposed action in the event of an accident. Whether this would work in an emergency is at the very least questionable. The authorities’ experience with comparable incidents is limited. When explosions occurred during geothermal drilling at Lake Albert in Kibiro on the night of 29 March 2020, the heavy metal-contaminated waste had not been removed even months later, as was shown by a subsequent investigation supported by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

Resistance

Oil production in a country where oil has never been produced before, without experienced authorities that can react quickly in cases of emergency, and in one of the most biodiverse regions of the continent: risky to say the least. An increasingly global movement has therefore formed against the project, which is also trying to influence potential investors and companies outside Uganda. Several reinsurers, including the German Hannover Re and the French SCOR, have already announced that they will not insure the project. But while many international NGOs are noisily warning about the climate impact of the project, local activists must struggle with the personal consequences of their activism.

One such local activist is a young man who fled Uganda to Germany to escape arrests and threats, at least for a while. When he first responds via encrypted connection, he has just been housed in North Rhine-Westphalia, with the help of a protection programme for persecuted human rights activists funded by the German Foreign Office. The Tagesspiegel has written confirmation from the protection programme. He makes regular anonymous blog posts when local civic organisations are targeted.

He publishes details of arrests at gatherings, calls to radio stations denying him airtime, smear campaigns. “In the end, I even learned that attacks were being planned against me,” he says. Not an isolated case: since 2020, Amis de la Terre has documented 40 attempts to intimidate or arrest local actors. One had to spend 58 nights in prison. Oxfam also points to numerous cases, including the arrest of an Italian journalist in 2021 while researching the project.

Total says it considers the protection of human rights defenders important and, where appropriate, tries to exert its influence on stakeholders and third parties itself, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. After being informed by the International League for Human Rights on 25 May 2021 that a member of Afiego and a foreign journalist had been arrested by the police in Buliisa, the company had taken the initiative with the local authorities and informed the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Uganda. They also wrote a letter to the Ugandan President demanding that the rights of the individuals concerned be respected. The Ugandan state oil company Unoc and the national oil authority did not respond to enquiries about human rights violations at the time of going to press.

The anonymous activist says via video call that local organisations are too ill-equipped to take action against such opponents. New laws are systematically used against NGOs - under the pretext that they are harmful to the government or are terrorists. The NGO Afiego, for example, is to have its licence revoked, as well as 22 other organisations.

This makes it all the more important to offer local people better opportunities to exercise their rights and to defend themselves against unfair compensation. Once oil production begins, the interest of the big donor-funded NGOs from the West is likely to wane. But it is precisely then that people need to pay attention. “I will train as many people as possible to resist peacefully and to raise funds so that it is no longer enough to take action against me.”

Tilenga and Kingfisher are just the beginning, the human rights activist believes. Uganda’s President Museveni said in a speech on 11 April 2022: The pipeline could be the nucleus of even greater development if Congo and South Sudan decided to use it too. There is more oil there. Once there is a pipeline to the sea in Tanzania, drilling there also will suddenly become more realistic.