Fossil fuel:

Is Africa’s coal boom just getting started?

Around 1.2 billion people live on the African continent. By 2050, that number could more than double to 2.5 billion. At present, more than 500 million people on the continent have no electricity. However, the continent’s energy needs are rising as the population continues to grow.

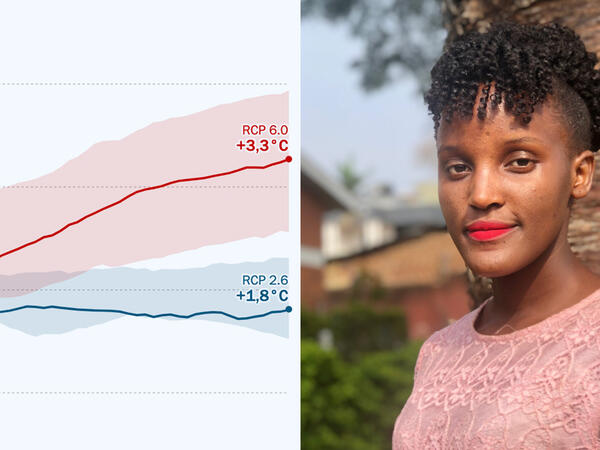

Whether this results in an increase in greenhouse gas emissions depends on whether new fossil-fuel power plants are built. Coal-fired power plants are particularly harmful to the climate. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the international community would have to permanently and effectively end coal-fired power generation by 2040. The entire continent of Africa (made up of more than 50 countries) was responsible for only about 4% of global CO2 emissions in 2019. However, dozens of new coal-fired power plants are expected to be built in coming years which would significantly increase CO2 emissions.

South Africa and Zimbabwe have big coal plans

Over the next few years, more than 20 new coal-fired power stations with a combined capacity of more than 47 gigawatts could come online in Africa, according to data from the U.S.-based environmental organisation Global Energy Monitor. In comparison, Germany’s lignite and hard coal-fired power stations had around a combined 38 gigawatt capacity as of March 2021.

Some countries really stand out when it comes to planned coal-fired power capacity: South Africa (4.1 gigawatts), Zimbabwe (4.2 gigawatts), and Botswana (1.7 gigawatts) in particular. What’s more, several gigawatts of coal-fired power in Africa have been delayed or postponed, but are still planned. Egypt has up to 12.6 gigawatts planned, for example.

New coal-fired power plants typically have a lifespan of 40 years or longer - so they emit greenhouse gases for decades. They often prevent climate-friendly alternatives. In 2016, nearly 70% of South Africa’s energy came from coal.

Across the globe, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels have risen over recent decades. China, the U.S. and the European Union are the worst offenders, while emissions from African countries are far lower. Overall, coal is responsible for the largest share worldwide: it accounts for 40% of CO2 emissions, followed by oil with 34%, and natural gas with 21%.

As early as 2025, some 50 sub-Saharan countries could bring new coal-fired power plants online. Together, these plants would be responsible for an additional annual emissions total of more than 100 million metric tons of CO2, as claimed in a study published in the journal ‘Nature Climate Change’. The study, led by researcher Jan Steckel, was produced at the Berlin-based climate research institute MCC.

Coal-fired power plants with capacities of almost 5 gigawatts are already under construction in Africa, as shown by data from the Global Coal Plant Tracker. Plans for power plants with capacities of 28.8 gigawatts have been postponed, for now.

The increase in emissions is still relatively small, amounting to one-seventh of Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. However, the researchers also comment that “trends in energy sector investment point to a more significant role for CO2-intensive coal and thus more emissions in the future.”

Pointing to China as a country that has “lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in just 20 years”, the report also emphasises that the country has witnessed unprecedented growth in coal energy. In 2020, China produced more than half of the world’s coal energy according to analysts at the think tank, Ember. China has by far the highest coal-related CO2 emissions. Africa’s emissions, as a continent, are far lower. Although the continent’s emissions are increasing, the entire continent only emits double the CO2 as Germany.

In 2020, China was operating around 1,000 coal-fired power plants. Africa, by comparison, was running just 34, 19 of which were in South Africa. Wind and solar power exist as alternative energy sources and energy storage technologies. But what would it take to drive the development of a sustainable energy systems on the continent?

Support is needed for change

Primarily, external investment is required. Jan Steckel mainly focuses mainly on how developing countries impact climate protection. “To ensure that renewable energies are also used and expanded in Africa, the risks for foreign investors must be mitigated”, he told The Tagesspiegel in response to a question. This is possible, he said, through so-called ‘export guarantees’. Here, the state protects the investing energy company against defaults, for example, if the solar power plant is built abroad, but the hosting country does not want to buy the electricity it generates. In Germany, these state export guarantees are known as Hermes guarantees.

But that’s not all, says Steckel: “second, states themselves need more stable conditions for the development of renewable energies. These can be contracts in which the country secures the purchase of the electricity, for example through feed-in tariffs.” This means the electricity supplier receives a fixed payment when it feeds electricity from renewable sources into the grid.

Vietnam could make the switch to renewable energies

Vietnam is one of the countries which provide an example of how to make the switch to renewable energy work. “For a long time, the Vietnamese government assured investors in coal-fired power plants that they would buy the electricity they generated in this way for several years at a fixed price”, Steckel explains. By contrast, investors were only offered renewable energy guarantees which expired after one year.

That’s all changed. Starting in 2019, he says, Vietnam began to strengthen the incentives for renewable energy development, including a feed-in tariff. “This led to a real investment boom. In just a few months, several gigawatts of renewables have been added. Now it looks like new coal-fired power plants can’t compete in Vietnam.”

Above all, renewables need money

Export guarantees and stable investment conditions are vital for renewable energies in Africa, but other structures are also required: “renewable energies also need the right infrastructure and storage facilities to compensate for fluctuations”, Steckel says. Fluctuations in power generation occur because, quite simply, the wind blows at different intensities, and the sun doesn’t always shine brightly. To build such an infrastructure, he says, countries need technical support and expertise, as well as capital.

The latter financing issue, he said, is where China plays a major role. “China is using loans to finance many fossil fuel power plants in Africa, sometimes with very unfavourable terms. Here, the international community need to look at what financing models are attractive for African countries in renewable energy.” Ultimately, he said, there will be massive investment in more energy on the continent in the near future. “African countries must be able to continue to expand their energy production. It can’t be a goal of climate protection to put that in doubt.”

“All new coal-fired power plants are highly problematic”

It will not be easy to reconcile climate protection with increased energy demand. Several gigawatts of coal-fired power in Africa’s energy sector are already planned or under construction. However, Charles Gymafi Ofori of the Africa Centre for Energy Policy based in Ghana, still believes a rethink is possible. “African governments should focus on producing clean energy technologies. This should ensure that African countries do not simply become consumers of energy when many of the mineral resources for renewable technologies exist on the continent.” Africa’s soils are rich in metals needed for the production of solar cells or battery storage, including aluminium, cobalt or copper. African governments would therefore need to invest in the research, development and production of such energy technologies.

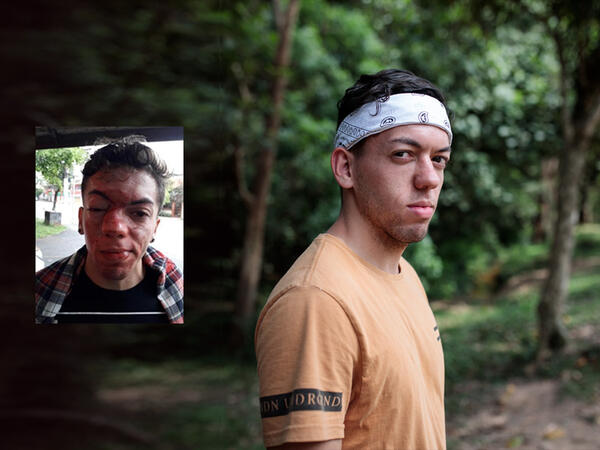

But Ofori is also clear that coal isn’t something that can be done without completely. “For a continent where millions still live without electricity, fossil-fuel power generation remains important to drive economic growth over the next three to five decades.” According to Ofori, the transition to a sustainable energy system must primarily alleviate energy poverty.

Climate protection and coal don’t mix

Other experts fear that new power plants in Africa will make climate targets unattainable, like Rainer Quitzow of the Potsdam Institute for Transformative Sustainability Research (IASS). “A speedy global phase-out of coal power is needed to achieve the Paris goals”, he says. These state that the world should limit global warming to no more than 2 degrees, or better yet, 1.5 degrees Celsius. “From this perspective, all new coal-fired power plants are highly problematic. They will continue to emit CO2 even when a complete phase-out should already have been completed.”

According to Quitzow, “the global climate and African countries will be affected if the latter don’t start now on climate-friendly development paths.” To do so, he said, poor countries in Africa would need major financial help to facilitate investment in renewable energy.

Upcoming climate conference to make money flow

This year’s UN climate conference in Glasgow in November should ensure that capital actually flows to African renewables. One of the goals of the conference is for industrialised nations to fulfil their pledges and provide at least 100 billion U.S. dollars in funding each year to help developing countries adapt to the consequences of the climate crisis. This includes building a climate-friendly energy system.

An OECD study last year showed that rich countries contributed only $78.9 billion to this climate finance in 2018. It also showed that donor countries are frequently giving loans instead of grants. Whether rich countries will stick to their promises and deliver at the UN climate conference in November remains to be seen.