Who is damaging the climate most - and who suffers the consequences

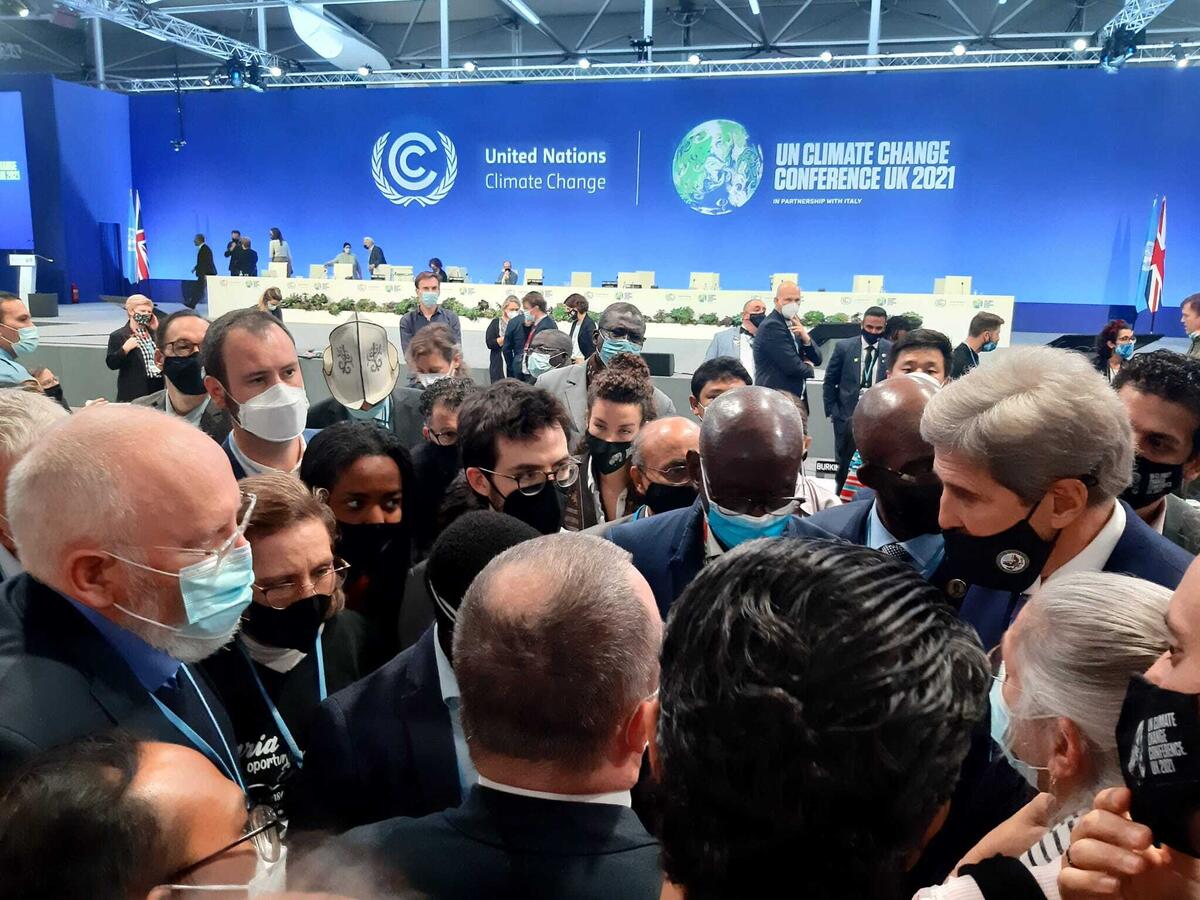

This was precisely one of the questions addressed at the UN Climate Change Conference “COP 2021” in Glasgow. But the very premises of the conference show that the historical responsibility for climate change is largely ignored. African states are largely underrepresented, the polluters are haggling for their own supremacy. And many negotiators from African countries could not even travel, some because of Corona restrictions, some because of visa problems.

Against displacement at 23

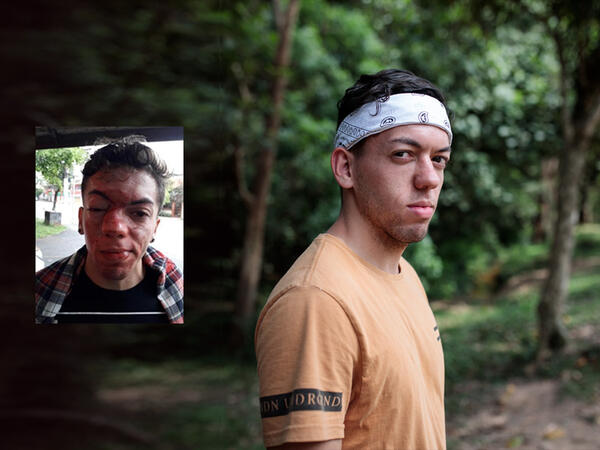

One of those who was there, nevertheless, is Lina Yassin. The 23-year-old is a member of the Sudanese delegation. As a delegate from her home country, she sat at the tables, negotiated for days, tried to make herself and her country heard. Not so easy as a representative of one of the poorest countries.

In photos, the 23-year-old can be seen discussing, explaining, negotiating. In one, it looks as if she is drowning in the crowd: almost like the country she represents.

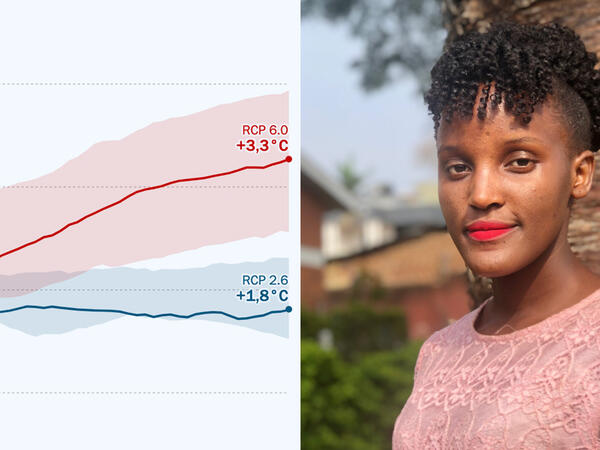

Sudan and South Sudan cannot help the increasingly frequent floods, Kenya and Madagascar cannot help the droughts. The greenhouse gases originate in other parts of the world. 20 wealthy countries cause 80 percent of emissions.

“You lose confidence”

This is what Yassin says about the COP in the aftermath. She knows the conference well, and has been attending for several years. When she says this, she sounds both energetic and disillusioned. The latter because the wealthy states, the so-called “developed countries”, committed a breach of trust on the very first day: in 2009, they had promised to provide the developing countries with more money every year. Money so that they can better cushion the consequences of climate change. One hundred billion was to flow every year from 2020 onwards. That was the plan.

Right at the beginning of the COP, however, the word came down: it won’t work. The rich countries are now giving themselves three more years. From 2023 onwards, the full amount is set to pour in each year. For many of the poorer countries, this is a bitter disappointment, Yassin says over the phone.

What is worse, she says, is that this gives the impression that in the climate crisis we cannot rely on those who have the opportunity to change something. “Developed countries don’t keep their promises” - she heard this phrase again and again at the negotiating tables and in the corridors.

This has overshadowed the negotiations, says the activist, who writes for Sudanese newspapers, works for the Climate Tracker project and is doing her Master’s degree in Oxford, UK. The rich countries have not kept that promise, so why should they be trusted in the future? Now, Yassin says, it is even more important to watch closely whether the decisions of this year’s COP are actually implemented. She will. Her future is at stake.

Ban Africa from making emissions?

In fact, action from poorer countries is needed - also by the global North - to end the climate crisis. As such, climate change holds the potential for new international conflicts. For instance, many emerging African countries could only now begin to make money from their natural resources, said Senegalese President Macky Sall recently. Reducing investments in the fossil gas sector would be “a fatal blow” to his country’s economy. But fossil fuels damage the climate. So should potential wealth stay in the ground?

A dilemma. Preventing African countries from extracting crude oil, for example, and thus strengthening their economies, is “definitely not fair”, Yassin also says. “You can’t just ban developing countries from making emissions!” She calls for compensation payments to poorer countries that voluntarily renounce the extraction of climate-damaging raw materials - there is no other way.

So far, rich states have made hardly any response to this. Even the historical responsibility for climate change is not being prominently addressed, says Yassin. In the negotiations, they behave defensively. “They shouldn’t always be pushing back ideas and proposals, not always trying to pay less money or keep fewer promises.”

This is what is most frustrating: the fruitlessness of the negotiations, their slowness. This contrasts with the urgency of the situation. “You sit there and discuss a paragraph, a sentence, a word for hours.” After a short pause, she says: “This is not just about politics. It’s about countries dying.”

Whether she will even be able to participate in the next COP, she does not know. At the same time as the conference, the military in Sudan was seizing power. Yassin was suddenly a delegate of a government that no longer exists.