From rice to chocolate: Germany’s food supply depends on these countries

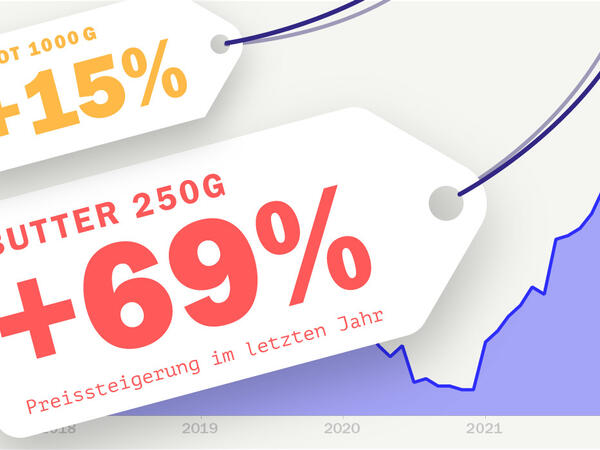

Russia’s aggression is creating victims of war in Ukraine. It is also creating victims of hunger globally. Sunflower oil, the most common oil used for example by a quarter of Indians, rose 16.7 percent in price between February 2022 and May 2022. India, the largest importer of edible oils in the world, imports 74 percent of its sunflower oil from Ukraine. No sooner did the war break out, than oil exports ran dry and trade prices soared. Consequently, India was forced to purchase more sunflower oil from Russia.

Food exports from Ukraine were disrupted either due to bans or forceful blockades of the ports in the Black Sea. This hit some countries very hard – like Moldova and Libya – since they significantly depended on Ukraine or Russia for some of their food supplies. Read more about these countries here. The war has once again demonstrated drastically, how globally interdependent our food consumption has become. And that is not only the case in India or Moldova, but also in Germany and the rest of Europe. Now, with another conflict in Taiwan on the horizon, the question is: Which countries does Germany most depend on?

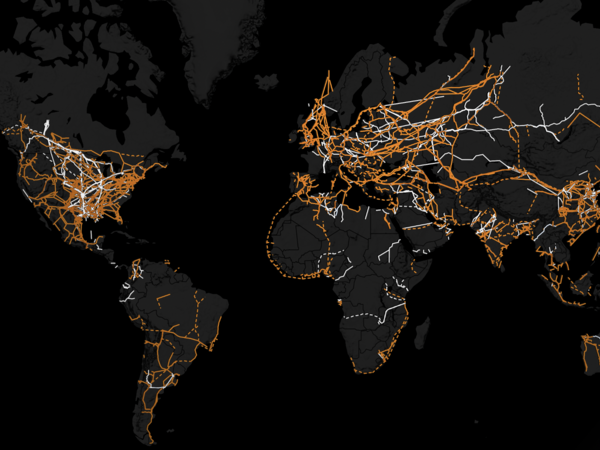

Different countries grow different food products depending on various reasons and factors, like climate or preference, and trade internationally. For example, as South Asia exports its rice globally, it depends on the world for its wheat. As globalization picks up pace, these inter-dependences grow complex; the number of products exchanged between countries has increased. They may grow deeper: some countries start to depend heavily on countable countries for certain commodities.

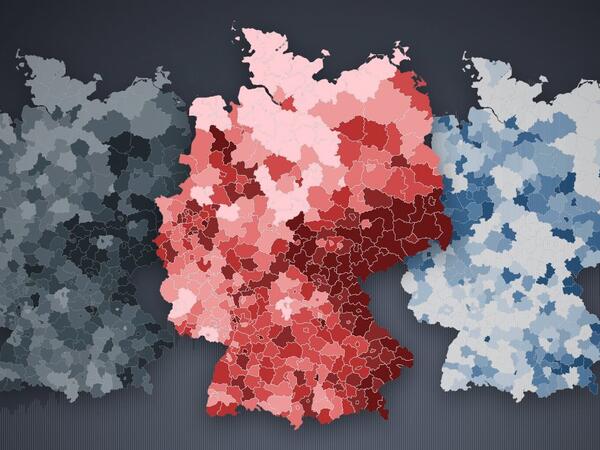

80 percent of food imports come from the EU

In 2020, Germany reportedly imported about 353 different food products from 175 countries, spending 95 billion USD on imports, averaging 91 billion USD over 2011 and 2020 annually. It spent most on ‘crude material’ (4.9 billion USD) (like tubers, plants, shells, animal derivatives, etc.), followed by whole cow milk cheese (4.5 billion USD) and ‘food pre nes’ (3.6 billion USD) (crop and livestock products, amongst other soups and broths, ketchup and other sauces, mixed condiments and seasonings, vinegar and substitutes, etc.). Not surprisingly, next on the list was wine (2.9 billion USD), 75 percent of which came from Italy, Spain, and France. A close follower was coffee, 66.3 percent of which came from Brazil, Vietnam and Honduras.

Overall, almost 80 percent of all food imports come from an EU-country. The highest value comes from the Netherlands with 23 billion USD. The next biggest exporters to Germany are Italy, Poland, France and Spain. But also, the US and Brazil play a decent role in the food supply.

Germany has limited import dependences on Ukraine. In fact, Germany runs a net trade surplus with Ukraine, and only remains slightly dependent on it for two products – maize and rapeseed. In 2020, Germany imported 74.5 million USD worth of maize (10.3 percent of its import quantity) and 174.7 million USD worth of rapeseed (6.7 percent of its import quantity).

Germany’s dependences on Russia are rather indirect. While Russian imports only form 0.2 percent by value of Germany’s all imports over the decade (2011 – 2020), Germany’s dependence for sunflower cake (that is used as animal fodder and fertilizer) has grown significantly over the years. In 2020, they were worth 48 million USD (45.4 percent of its import quantity). Its shortage has naturally caused animal feed prices to inflate nationally. However, the German government has already been finding ways out. Other notable dependences on Russia include distilled alcoholic beverages, tobacco, mustard seeds, and some oils. Some historical dependences like maize (from 34 million USD in 2014 to three million USD in 2020), linseed, rapeseed oil have gone down over the years.

Political and economic dependences

Limited dependences on Ukraine and Russia have come to serve well during the war. But what guides these moves? Sometimes they may be economic. Consider Poland to whom Germany has turned for its cigarettes over the years. The value of imports rose from 143 million USD in 2011 to 1.2 billion USD in 2020. While Poland has always had a notable share in German cigarette imports, this has now significantly increased to 75 percent of cigarettes (by quantity) in 2020. Subsequently, cigarettes imported from Romania and the UK have been reduced. In 2021, Poland offered the second lowest price for a cigarette pack in the European Union at 3.94 EUR after Bulgaria (3.07 EUR).

Sometimes import dependences could also be political. For instance, Germany has consistently diverted its import of tomato paste from China from 21 million USD in 2011 to 1.5 million USD in 2020, sourcing the deficit from other European nations instead. Later, this came within the backdrop of the accusations in 2019/2020 that China was forcing labour from persecuted minorities like Uyghurs in Xinjiang to produce tomato products. German imports of tomato paste fell from 4.7 million USD in 2019 to 1.5 million USD in 2020 while it saw over 100 percent rise in imports from each the Netherlands, Austria, Ukraine and Hungary.

Biased sensitivity

This “political sensitivity” nevertheless seems to be quite biased at times. For example, Italy remains the top exporter of tomato paste to Germany. However, Italy, especially regions in its south, has been alleged of forced labour in tomato harvests that are often sold in national and international markets. The international food and drinks company Princes and Oxfam Italy have recently partnered to support the on-going effort in protecting tomato worker rights – whether these considerations are part of Germany’s reliance for tomato in Italy is worth exploring.

Germany’s imports have also taken their course in responding to agricultural regulations over the years. For instance, in 2011 India formed ten percent of Germany’s husked rice (brown rice) imports. This peaked in 2012 with a 19 percent share of imports. By 2020, however, the share fell to only four percent. This change likely came in response to the stringent EU rice import rules introduced and implemented between 2017 and 2018 that reduced the maximum permissible residue level of Tricyclazole (a fungicide) in basmati rice. Between 2016 and 2017, the imports of husked rice imports from India had halved and dropped further. Instead, this supply was directed through Germany’s top trading partner: the Netherlands.

The special bond between the Netherlands and Germany

Nothing comes close to the scale of bilateral trade between the Netherlands and Germany. Imports from the Netherlands formed 25 percent by value of German imports over 340 products in 2020. On average, this means 22 billion USD annually over the decade. The Netherlands is a unique case because it is not only a resilient agricultural producer but also a major re-exporter hub for Europe. As a re-exporter, it imports from the world at its ports, processes it in limited ways, and exports it again to European countries. Some products largely re-exported to Germany from the Netherlands include chocolate (and cocoa beans, cocoa butter, cocoa paste), oranges, banana, avocado, mangoes, and many other fruits and juices. This way, Germany’s dependence on the Netherlands is unique and critical since it becomes its gateway to the world, in addition to supplying it with its own products.

The case of husked rice explains this well. After Germany could not directly source its rice from India for regulatory reasons, the Netherlands was likely to be a passage through which it could. Six months after the EU rice regulations were enforced in early 2017, an Indian company ‘LT Foods’ set up its first ‘rice processing plan’ in Rotterdam, manufacturing wide range of rice, like basmati, jasmine, Thai and American with a 60.000 tonnes capacity. The location (the Netherlands) was deemed critical because it provided easy access to the whole of Europe and the UK. This project was set up in collaboration with Rotterdam Partners, the Port of Rotterdam Authority and the Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency. By early 2020, the company was flourishing, investing in new rice packaging lines at a site in Maasvlakte (a port complex), placing it ideally to import rice from India for distribution in Europe.

The chocolate supply depends on two countries

Imports of cocoa beans also explain well the role of the Netherlands in Germany’s gateway to the world. In 2020, Germany imported 30.7 percent of its beans from the Netherlands and 31.3 percent directly from Côte d’Ivoire. But the Netherlands itself imported 48 percent of its beans from Côte d’Ivoire. This implies Germany’s dependence on Côte d’Ivoire for these beans is at least 31.3 percent and at most 62 percent. If we also account for Belgium that imported 56 percent of its beans from Côte d’Ivoire, then Germany’s dependence goes up to 84 percent (Germany imported 22.4 percent of its beans from Belgium in 2020). If trade is disrupted at the Netherlands for some reason, supplies could be directed to other ports like Belgium to reach Germany. But if Côte d’Ivoire falls out, inevitably chocolate’s availability in Germany will too.

Therefore, it is necessary to look at Europe with its many gateways as a collective unit to point out regions in the larger world that Germany eventually depends on.

In 2020, Europe (40 nations) imported food products worth 141 billion USD from 153 countries outside Europe. The Netherlands alone imported 20 percent of this value. About 50 percent of these European food imports came from only nine countries: Brazil, the US, Turkey, China, Indonesia, Argentina, Côte d’Ivoire, India and Canada.

Half of these imports consisted of only 17 products. A great deal of these outer-EU products are coffee from Brazil, soybeans from the US as well as distilled alcohol from the US and the UK. Some dependences have also been shifted to Europe – like palm oil. Over the decade, Germany has shifted its direct purchase of palm oil from Indonesia onto re-exports via Italy that itself imports from Indonesia and Malaysia. The share for re-exporters like the Netherlands and Belgium has also gone up. Germany, however, has reduced its import of palm oil over the years.

While most of German food imports have remained eurocentric over the decade, the wider connections show the global entanglement of the food supply chains. Hence, it is essential for Germany’s food security to ensure the stability of Europe and the few countable countries beyond the region’s borders. A crisis in these countries could pose some risks but may not be a direct threat. Instead, the real threats lie in indirect products that aid Europe’s agriculture – like energy and fodder. The Ukraine war has also brought this issue to the forefront and perhaps it is time for Germany and Europe to act towards fixing these pressure points before they re-emerge.