Berlin, the rental market lab:

How international investments are upending the housing market

A strange phenomenon has been observed in London for some years now. When it gets dark, only a few lights go on in the windows of particularly sought-after residential areas in Covent Garden or Chelsea. The apartments belong to a cosmopolitan elite that owns properties in several cities and only uses them during their infrequent visits to London. Financially, it’s still worth it. They are good investment properties, even when unoccupied.

Paris also empties out in the evening. The number of available apartments there is falling because running offices in the city centre has been considered more lucrative. Another 114,000 have been converted into furnished apartments for tourists. These, too, stood empty during the pandemic.

Berlin, new housing market pioneer?

Berlin lies on the other side of the spectrum. In the European capital of self-actualisation, where 83 percent of the population rent their accomodation, buying your own apartment has long been considered unprofitable, unnecessary or at least bourgeois. As average incomes rise, many argue that Berlin, too, is becoming an proprietor-occupied city, just as has been the case in Dublin, Madrid or Oslo for generations. But a Europe-wide investigation shows that could be a fallacy.

Madrid and Oslo may not be harbingers of what’s in store for Berlin, but quite the opposite. Berlin, with its housing corporations, failed rent cap and angry referendum, is not a relic, but a taste of what is to come: a European housing market and housing crisis intricately linked to the financial market. Berlin is the laboratory for this, with a connection to the empty apartments in London and the empty offices in Paris.

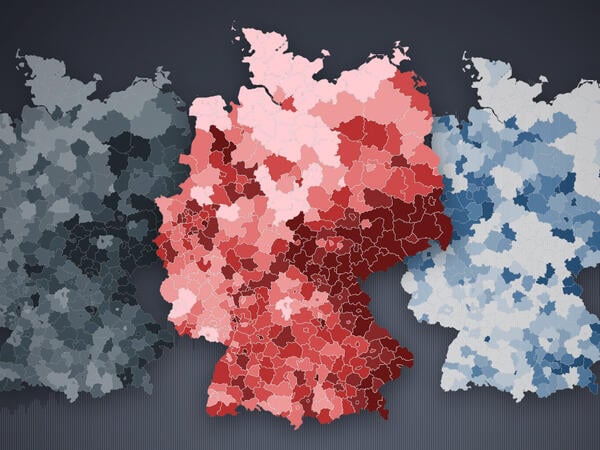

Over seven months, our research network compared the housing markets in 16 European cities. We wanted to know what the biggest private housing companies in each city are, as well as whether similar developments are becoming apparent, and whether there are companies that are already operating across Europe. The research project, called “Cities for Rent” is coordinated under the umbrella of “Stichting Arena for Journalism in Europe” and is funded by the Investigative Journalism Fund for Europe.

The rise of the cities and slowly rising salaries

The results: the housing markets in each participating city are structured far differently than initially assumed. But even though there are no Europe-wide housing megacorporations as of yet, the first ones are just emerging. Their approach is similar in the different cities and politicians there are equally perplexed. The market forces behind this are the same everywhere and are being accelerated by the pandemic.

First, the population in all 16 cities has been growing in recent years – in some cases very strongly. The only exception is Athens. Secondly, rents are rising in all cities, even in shrinking Athens. According to the Eurostat index, rents across Europe in 2020 were 14 percent higher than in 2010, and purchase prices were 26 percent higher.

Although median incomes have also risen over the same period, they have risen less in many metropolitan areas than in the rest of the country. Housing costs have also risen more sharply there. According to the German Institute for Economic Research, rent in Berlin witnessed a 64 percent increase between 2010 and 2019 for existing buildings and 51 percent for new buildings. In Neukölln, there was even a 146 percent increase in asking rents between 2007 and 2018, according to Immoscout24.

Hardly any Europe-wide comparison of cities exists when it comes to rents. This is because there is no European approach. Eurostat, the highest statistical office, can only ask cities to report voluntarily. Few do. As a result, the only comparative figures are mostly investment reports; knowledge of the market is exclusive. Even EU parliamentarians report that they don’t have any precise information about which groups are active in the housing market and where in Europe.

New apartment, tough decision

Thirdly, the proportion of households living in rented accommodation in the 16 cities is well above the national average. The only exception is Dublin, where just 23.9 percent of the population rent their accomodation. But even there, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to buy. In a Eurostat survey, only 15 percent of the population in Dublin say it’s still possible to find an apartment. This puts Dublin, a proprietor’s city, and Berlin, a city of tenants, almost on a par. The fact that many people seek ever larger apartments only exacerbates the problem.

Fourth, in most countries, the proportion of the population renting their homes is increasing, while individual home ownership is declining. Fifth, there is also tourism to consider and the associated conversion of apartments into Airbnb accommodation. And sixth, cities are not able to build enough new apartments to slow the price of developments, whether or not they have strong or weak tenant protection laws.

The new flow of money

In the last ten years, these six factors have now been met by the most serious one. According to research, it’s money, lots and lots of money. Not the paltry amounts from building savings contracts, but billion-dollar capital funds, which apartments were once to be too small for. Real Capital Analytics, a leading global analysis company for real estate transactions, collects information on large apartment purchases worldwide. For this research, the company evaluated all large real estate deals in the 16 cities.

In 2007, the total of large purchases (at least ten residential units per purchase) was 17.3 billion euros. In 2009, investments fell to just under eight billion during the financial crisis. Since then, they have exploded. In 2019, investment in rental apartments stood at 66.9 billion euros. Even during 2020 when Corona hit, investments only declined slightly. And the number one city in terms of investment was Berlin.

A total of 42 billion euros was spent on major residential deals in Berlin and the surrounding area between 2007 and 2020, more than in Paris and London combined. In contrast to London, most of the investment in Berlin still came from within Germany. However, the analysis of the countries of origin for cross-border investments shows that investments are slowly globalising, with the US in first place. But Germany, France, England and Sweden also invest a lot cross-border. Qatar and Russia are also in the mix. And as the number of bids increases, the higher the prices rise.

“I think by now it’s absolutely clear that the housing crisis affects everyone in Europe, not just a small group of people,” says Kim van Sparrentak, a member of the EU Parliament for the Dutch Green Party. She collaborated on a report on the housing situation. The crisis is the result of European policies that have only ever asked how to strengthen the market, she says. Tom Leahy, senior analyst for real estate transactions at Real Capital Analytics, dissects the situation far more soberly: really big investment capital is running out of key investment options.

The financial crisis has changed the housing market, and now Corona adds to it

According to Leahy, the real estate market after the global financial crisis is completely different from the one prior. If you have to invest really high amounts of money, a pension fund worth billions, for example, you can’t invest all your money in stocks or currencies. The fluctuations are too high and the risk too great. An important portion of pension funds, asset management companies and rich family offices was therefore traditionally invested in low-risk government bonds. However, since the European Central Bank ultimately ended the financial crisis by setting the key interest rate at zero, many government bonds now offer only minimal interest rates, often even negative interest rates. This makes investments in real estate even more attractive.

For a long time, apartments were not as popular for these types of investments, says the analyst, “If you plan to spend 600 million euros on European apartments in the next two years, you have to buy a lot of them.” Commercial real estate, offices or shopping centres were therefore the investment of choice. But the growth in online shopping is leading to empty stores, and home offices are replacing offices. Everyone needs an apartment, however. And despite the crisis, 90 percent of rents continue to be paid, says the analyst, with the support of government aid programs. Thus, apartments act as an investment with regular, secure returns.

Perpetual motion

The popularity of cities and people moving more often also leads them to rent for longer periods in their lives on average, says Tom Leahy, who went to buy his first apartment of his own a few days after the interview. He recently looked at purchases by the world’s 50 largest investment managers, Blackstone, Allianz and Generali, for example. According to the report, 30 percent of their real estate investments went into the residential market last year , compared to only around ten percent in 2007. From Leahy’s point of view, Germany is therefore a mature market. And others will follow.

The flow of money into the housing market is becoming a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Because housing prices are rising, fewer people can afford one. Those who still can will try to buy one anyway for fear of rising rents, which will raise prices even more. In the long run, therefore, more people are more likely to live in rentals. And that makes apartments even more profitable from an investment perspective.

That’s the view from the top. At the bottom, where people call apartments homes, not investments, the shift in capital is leading to deep cracks in urban life. Because before apartments can be bundled into packages of hundreds, then thousands, and before they are renovated, rented out and traded on, those who live in them are often in the way.

“Cities for Rent” is a European research project. All members work independently, but research results are shared. It consists of 16 teams in 16 European capitals and metropolises in 16 countries (exact list of media and journalists below). For seven months, the research network examined local housing markets, researched data on large housing companies, price trends, investments and demographic developments in the individual cities and compared common structures.

What was Tagesspiegel's role in the project?

The Tagesspiegel Innovation Lab is the Berlin portion of this research and publishes the research results in Germany. In addition to local research into the Berlin housing market, the team developed the visualisations and a joint design concept for the collaborative project. The interactive comparative graphics can be used by everyone, translated and classified in the respective national language. An overview of all publications can be found on the project page at Arena Journalism for Europe..

Participating partner media and research organisations

Vienna: ORF, Brussels: Apache, Prague: Deník Referendum, Copenhagen: Information, Paris: WeReport, Mediapart, Athens: AthensLive, Reporters United, Dublin: Dublin Inquirer, Milan: IrpiMedia, Amsterdam: Follow the Money, Oslo: E24, Lisbon: Expresso, Bratislava: Aktuality, Madrid: El Diario, Zurich: Reflekt, Republik,

Other relevant research, publications and studies that were built upon for this study

Back in 2018, the Tagesspiegel and the non-profit research centre Correctiv launched the project Wem gehört Berlin. Together with all Berliners, the team wanted to find out who owns the houses in this city in order to create more transparency in the Berlin real estate market. This resulted, for example, in a story about a British billionaire family, that is one of the major secret owners of this city. We also set out to find out who ultimately profits from the Berlin rental market. In the European project, we were able to build on the findings from this research. The project Wem gehört...? in Germany was continued many times over. The project now exists in numerous German cities.

There was further relevant research into the Berlin housing market that we were able to build on. For example, the project Wem gehört die Stadt? (Who owns the city?) headed by tax expert Christoph Trautvetter, has since published new findings on the Berlin rental market in the form of various studies. The expert has provided the project with valuable insight.

The Berlin research project Mietenwatch also published analyses on which we were able to build.

The real estate analysis company Real Capital Analytics prepared an evaluation of investments in the participating cities for the European research, which it made available to us free of charge.

We would also like to thank Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, which published numerous relevant data sets on the European housing market and responded to numerous queries about data sources.

What's next for the research?

Further publications will follow – in the Tagesspiegel – and in the project's European partner media. In addition, all publishable datasets from this research will be published on a central page of Arena Journalism in the medium term to facilitate future research on the housing market in Europe.